By Republic Project Staff.

January 18, 2026 – Revised January 20, 2026

Related Reports:

The REPRO Source Report: Utah at the Brink – The Constitutional Crisis No One Saw Coming – Redistricting, Constitutional Authority, and the Limits of Legislative Power. This 139 page document is also available as a downloadable PDF with linked sections and citations. Click here: https://republicstratagems.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/repro_source_report_utah_redistricting.pdf

UT LEGISLATURE FORMAL BRIEFING: Redistricting

The Day Utah Lawmakers Forgot Their Limits and Treated the Constitution as Optional – The exact statutory text of Proposition 4 that clearly spells out the redistricting standards and obligations that both the commission and the Legislature must follow. can be accessed by reading the following article at UtahStandardNews.com

Revised January 20, 2026

Revised January 26, 2026 to include Addendum, How to Spot the Propaganda in the Debate, Constitutional Comparison, and An Open Message to City Councils and County Commissions.

Table of Contents

Navigation tip: The Table of Contents lets you jump to any section. To return to the top, scroll up and use the Table of Contents again.

- Table of Contents

- ADDENDUM: Before You Read Further, What This Fight Is Really About

- January 18, 2026 Original Post

- 1. What Did Proposition 4 Actually Do?

- 2. What Did the Commission Do – and Not Do?

- 3. What Did the Legislature Do – and Why Did It Matter?

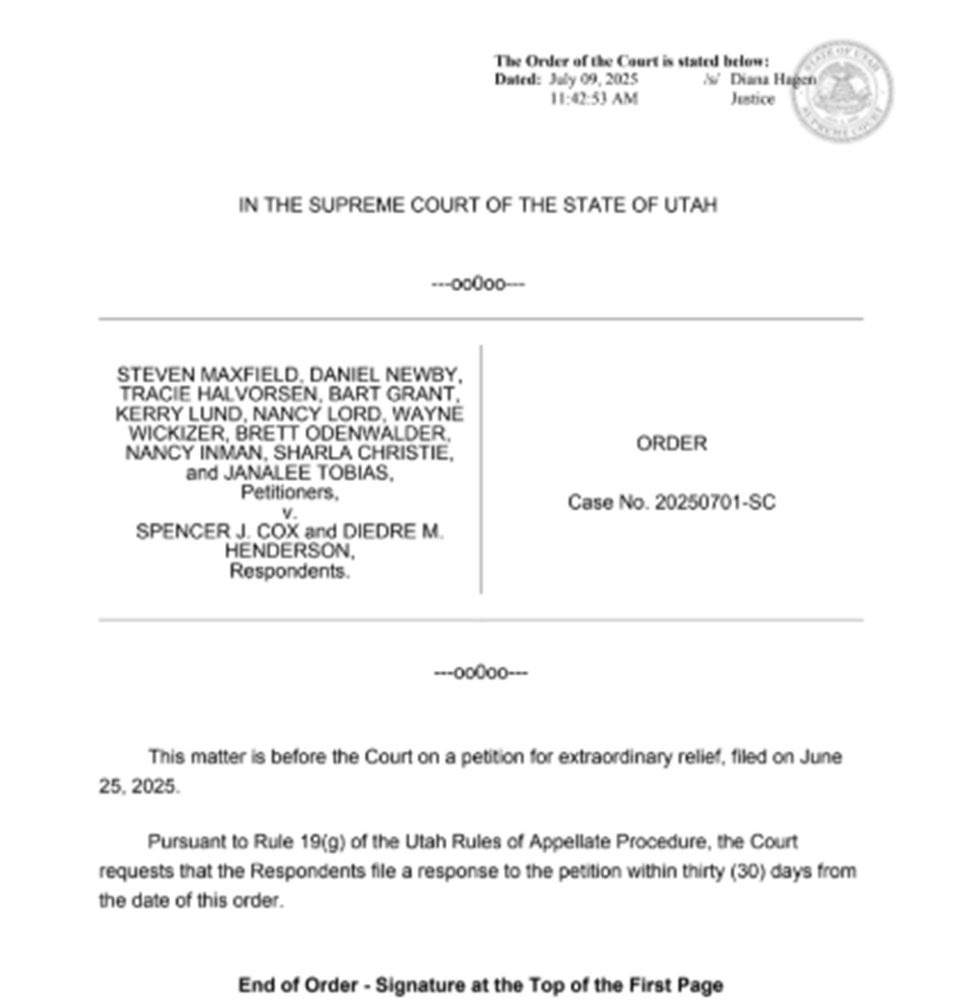

- 4. What Did the Court Do – and Did It Have Another Choice?

- The Irony at the Center of the Repeal Push

- Why This Fight Isn’t Going Away

- Utah’s history with initiatives

- The Bottom Line

- This is no longer a dispute about redistricting.

- In Summary:

- FAQ’s

- MORE QUESTIONS/ANSWERS

- 1. Did the Legislature’s 2025 map follow the guardrails of Prop 4, absent the commission?

- 2. Did Judge Gibson elevate her ruling into a de facto constitutional amendment?

- 3. Did the Utah Supreme Court elevate Prop 4 over existing statute?

- 4. Is it reasonable to say there are no checks and balances because MWEG (Mormon Women for Ethical Government) is not electorally accountable?

- 5. Does this set a dangerous precedent where activists can impose maps through courts?

- How to Spot Propaganda in This Debate

- CONSTITUTIONAL COMPARISON

- An Open Message to City Councils and County Commissions

- DUAL-LICENSE COPYRIGHT NOTICE for THE REPUBLIC PROJECT

ADDENDUM: Before You Read Further, What This Fight Is Really About

Over the past several weeks, Utah has experienced one of the most intense political fights in recent memory. This conflict is not about policy nuance or technical map lines. At its core, it is about who gets to decide who represents the people of Utah.

This is more than a routine legal spat. It is a contest over political power, playing out simultaneously in courtrooms, at the Capitol, through ballot initiatives, and now on the national stage.

That escalation has produced a coordinated response from Utah’s Republican establishment. In late 2025 and continuing into early 2026, Legislative leaders and party aligned actors are pursuing multiple legal avenues, including:

• A legal appeal challenging a judge’s ruling on newly drawn congressional maps, and

• A party supported ballot initiative that seeks to repeal Proposition 4 entirely, which would remove voter imposed constraints on the redistricting process and restore primary authority to the Legislature and governor.

At the same time, National figures have also entered the debate, including national activists, and Donald Trump, who publicly endorsed repealing Prop 4 and argued that congressional maps should be drawn by lawmakers rather than judges

These actions are neither trivial nor abstract. They go directly to the question of voters’ rights and constitutional fairness in elections.

This posture is reinforced by legislative action beyond redistricting. Walt Brooks, R–St. George, is sponsoring HJR13, a joint resolution that would amend the Utah Constitution to allow the Legislature to trigger special judicial retention elections for judges it deems “unfit.” Framed as accountability, the measure would shift removal leverage toward the legislative branch and introduce a political mechanism capable of pressuring judges in response to constitutionally grounded rulings. Brooks is also sponsoring a separate “Judicial Retention Amendments” bill currently listed as in process, the text of which has not yet been released. While its contents remain unknown, its pairing with HJR13 strongly suggests an implementing or companion effort to define standards, procedures, or triggers for such elections by statute. Taken together, these measures raise serious separation-of-powers concerns and invite scrutiny under legislators’ oaths of office, which require fidelity to the Constitution and preservation of judicial independence, not expansion of institutional dominance over a co-equal branch of government.

For voters, the significance is not procedural. It is whether constitutional guardrails survive coordinated political pressure across all branches of government.

This fight is not about Democrats versus Republicans. It is not about personalities. It is not even primarily about which party wins the next election.

It is about the Constitution and who holds power in a representative government.

Plain-Language Constitutional Explainer

Stripped of slogans and spin, the constitutional question is straightforward:

Can voters place binding guardrails on how politicians draw election maps, or can politicians remove those guardrails whenever they become inconvenient?

Utah voters have already answered that question once.

In 2018, voters passed Proposition 4, creating an independent redistricting commission. The purpose was simple and constitutionally grounded: to limit self-interest when politicians draw congressional districts and to protect voters from elections being engineered in advance.

That principle is not radical. It reflects the logic of checks and balances.

Under the Utah Constitution, citizens have the authority to legislate through ballot initiatives. When voters pass a law, it carries the same legal weight as one passed by the Legislature, unless it violates the Constitution itself.

The real constitutional issue, therefore, is this:

• If voters lawfully pass a reform to restrain political power,

• and that reform does not violate the Constitution,

• should elected officials be free to undo it simply because it limits their control?

That question is now being tested in court and at the ballot box at the same time.

Why This Moment Matters

The reaction to Proposition 4 reveals more than the initiative itself ever could.

Once Prop 4 began to meaningfully constrain redistricting discretion, nearly every level of Utah’s Republican establishment mobilized. That response has included state leaders, local party figures, organized party apparatus, and national activists and organizations. This level of coordination does not occur unless something significant is at stake.

The strategy is clear. If the legal path fails to overturn or neutralize the court’s map ruling, the fallback is to remove the guardrails entirely by repealing Prop 4. Repeal would return Utah to the system voters explicitly rejected in 2018, restoring broader control over district boundaries to incumbent policymakers.

This context matters. The intense focus on repeal, separate from the court appeal, suggests preparation for a future in which courts may uphold stronger limits on partisan redistricting. Running legal and political tracks simultaneously functions as a hedge against uncertainty.

What makes this fight unusual is not only the stakes, but the convergence of tactics:

• court orders altering maps,

• constitutional arguments about separation of powers,

• signature campaigns to undo voter-approved law, and

• direct involvement by national political figures.

Taken together, these elements reveal three realities that are difficult to ignore.

First, Proposition 4 works. It reduces political control over district lines, which is precisely why it is being targeted.

Second, the legal outcome is uncertain. If party leaders were confident that appeals alone would fully restore legislative authority, there would be little urgency to repeal Prop 4 outright.

Third, congressional control is part of the calculation. Court-ordered or commission-influenced maps could produce at least one genuinely competitive Utah congressional district. That possibility carries national implications and helps explain why outside actors have become involved.

None of this requires conspiracy theories. It follows basic political logic.

What the Repeal Effort Would Do

Supporters of repeal often frame their effort as a defense of representative government. The language is reassuring, but outcomes matter more than slogans.

Repealing Proposition 4 would:

• Remove voter-imposed constraints on redistricting,

• Restore primary authority to the Legislature and governor, and

• Return Utah to the same framework voters rejected in 2018.

In practical terms, it would give power back to the very institutions voters sought to restrain.

That outcome may be legal. But legality is not the same as constitutional integrity.

The repeal initiative still faces a high procedural bar. It must gather more than 140,000 valid signatures by mid-February to qualify for the ballot. Reporting indicates the effort is active but not yet complete, while counter-efforts are encouraging voters to withhold or withdraw signatures.

Why This Is Not About Party Loyalty

There is a familiar political narrative that Democrats pursue power while Republicans pursue money. Utah’s redistricting fight exposes the limits of that framing.

Here, the establishment appears focused on preserving influence, institutional control, and political advantage. This is not a grassroots revolt. It is a top-down campaign reinforced by paid signature gathering, coordinated messaging, and appeals to authority rather than to voters’ independent judgment.

Compounding the issue is a widespread awareness gap. Many Utah voters are not yet fully informed about what is at stake or what repealing Prop 4 would actually change.

Utahns are being asked, politely but persistently, to sign away a reform they already approved, often without clear explanation of what they would be relinquishing.

That raises an uncomfortable but necessary question:

At what point does trusting leaders become surrendering rights?

The Core Question

This is the question that ultimately matters, and it is not partisan.

Should voters be allowed to place durable guardrails on political power, or should those guardrails disappear the moment they inconvenience those in office?

Everything else, lawsuits, initiatives, endorsements, messaging, flows from that single issue.

For everyday Utahns, the key concern is not who wins a particular fight, but whether voter-approved reforms will be respected as law unless voters themselves choose to change them.

This publication has taken a position not for a party or a candidate, but for constitutional accountability. If reforms passed by voters can be undone through pressure campaigns before they are allowed to function, then voter power becomes temporary by design.

That is not representative government. It is managed consent.

Utahns deserve clear answers before they are asked to sign anything, answers grounded in constitutional reality, not slogans, tribal loyalty, or national personalities.

January 18, 2026 Original Post

Utah’s redistricting fight refuses to die because it was never resolved at the root. Voters were promised one thing, government delivered another, and now everyone is arguing about who has the authority to fix the mess.

Rather than drown citizens in legal jargon or partisan spin, here are four simple questions that cut through the noise.

1. What Did Proposition 4 Actually Do?

Proposition 4, passed by Utah voters in 2018, did not strip the Legislature of its constitutional authority to draw maps. What it did was impose statutory standards and guardrails on how that authority could be exercised.

Prop 4 created:

- An Independent Advisory Commission on Redistricting

- Clear anti-gerrymandering standards

- Requirements for transparency, public input, and fairness

The commission’s role was advisory, not binding. But the standards were binding. That distinction matters.

In plain terms: voters said, “You still draw the maps, but you must follow these rules.”

2. What Did the Commission Do – and Not Do?

Here’s where the process started to drift.

Although Prop 4 envisioned independence, most commission members were appointed through processes controlled by elected officials. Five of the seven members were selected by establishment-aligned actors with direct political interests in future elections.

The commission did produce maps. But:

- Its independence was constrained

- Its recommendations were ignored

- Its work was treated as optional rather than directive

Critically, the Legislature rejected the commission’s recommended map, not because it violated Prop 4 standards, but because it diluted partisan advantage.

That decision triggered the next step.

3. What Did the Legislature Do – and Why Did It Matter?

After rejecting the commission’s map, the Legislature passed SB200, which materially altered the voter-approved framework by turning the commission into a purely advisory body with reduced relevance.

That move became the legal fault line.

Why? Because Utah’s Constitution, as confirmed by the Utah Supreme Court, holds that voter-enacted initiatives carry equal constitutional weight to legislative acts. The Legislature cannot unilaterally rewrite them without voter approval.

This is where the phrase matters:

Managed noncompliance

There is no need to allege conspiracy. The pattern is enough:

- Partial implementation

- Structural weakening

- Procedural avoidance

- Then repeal when the system “doesn’t work”

Whether by intent, inertia, or political convenience, the result is the same: voters are told their decision mattered … until it didn’t.

This sequence highlights a recurring institutional pattern: partial compliance with voter mandates, followed by procedural alteration, judicial intervention, and subsequent political backlash. Whether intentional or not, the effect is erosion of public trust. The issue is not whether one map is preferable, but whether voter-enacted statutes are implemented faithfully or treated as optional. Conservatives concerned with constitutional order and rule of law should find that question worth careful consideration.

4. What Did the Court Do – and Did It Have Another Choice?

Once the Legislature failed to comply with Prop 4 as enacted, the courts were pulled in, not as activists, but as referees.

In 2024, the Utah Supreme Court ruled clearly: Prop 4 was valid law and had been unlawfully altered.

The lower court was then faced with a hard reality:

- Election deadlines were imminent

- The statutory process had been broken

- There was no time to rebuild the commission from scratch

So the judge did what courts do in remedial cases:

- Applied criteria derived from Prop 4

- Reviewed competing maps

- Selected the one that most closely met the standards voters approved

Was it perfect? No.

Was it ideal? No.

Was there a realistic alternative under the circumstances? Also no.

That’s why the court-ordered map remains in effect today, even as appeals continue.

The Irony at the Center of the Repeal Push

One of the loudest arguments for repealing Prop 4 comes from people saying, “The people should decide.”

Here’s the problem.

The people already did. In 2018.

Saying “the people should decide” while working to undo the last time they decided is not constitutional conservatism. It’s political contradiction.

If Utah politics had a Greek chorus, this would be its refrain:

“The people should decide which is why we must overturn what the people decided.”

That irony is the result of a system that has trained conservatives to distrust:

- Courts

- Initiatives

- Reformers

- Activists

- Anyone outside the Legislature

This argument unintentionally affirms the court’s reasoning while rejecting its conclusion. It exemplifies the confusion created when political messaging overwhelms constitutional logic. People are trying to reconcile principles that Utah’s political class has twisted beyond recognition.

This is why so many conservatives feel disoriented, why well-meaning voters have been whipped into a frenzy, convinced that constitutionality is illegality and that lawful judicial action is activism. The anger is real, but the facts are clear, the public acted lawfully, the judge acted lawfully, the Legislature is reacting politically. That distinction matters. This moment exposes the backward logic created when constitutional conservatives are pressured into defending positions that contradict their own principles.

When a political system trains conservatives to distrust the judiciary, distrust initiatives, distrust Democrats, distrust activists, and distrust reformers, eventually the only people left to distrust are… the voters themselves.

Why This Fight Isn’t Going Away

Republican legislative leaders have now asked the Utah Supreme Court to reverse:

- The restoration of Prop 4

- The invalidation of SB1012

- The court-ordered map currently in effect

At the same time, an initiative is underway to repeal Prop 4 entirely.

That combination tells you everything:

- First, weaken compliance

- Then call the law unworkable

- Then demand repeal

Utah’s history with initiatives

Utah’s history with initiatives and referendums shows they are neither casual nor easily manipulated tools of direct democracy. Over the past several decades, Utah voters have approved relatively few ballot measures, often by narrow margins and only after sustained public debate. Many fail outright. Those that pass usually do so in response to legislative actions perceived as disconnected from voter intent.

A clear example came in 2020, when citizens mobilized in record numbers to place a referendum on the ballot to repeal SB2001, a sweeping tax restructuring bill. Faced with overwhelming public opposition, the Legislature repealed its own bill before the vote occurred, rendering the referendum unnecessary. That episode illustrates a recurring pattern in Utah politics: when citizen action gains sufficient momentum, lawmakers often retreat rather than risk a public vote. This was not abuse of the initiative process; it was accountability functioning as designed. Historically, Utah initiatives that expand government power rarely pass without resistance, and those that do are frequently constrained or revisited. Against this backdrop, the redistricting dispute is not an outlier or a power grab by activists. It reflects the same constitutional pressure valve used sparingly when representative government fails to reflect voter intent. The crisis is not that initiatives exist, but that institutions increasingly resist them once they succeed.

This isn’t about maps anymore. It’s about whether voter-enacted laws mean what they say, and whether the Legislature is obligated to follow them. When lawmakers altered a voter mandate instead of complying with it or repealing it outright, they created the vacuum that invited judicial intervention and guaranteed the outcome conservatives now decry. The irony is that many are now defending the same institutional arrogance that produced SB54, an elite impulse that distrusted voters, sidelined grassroots reform, and asserted legislative supremacy over constitutional limits. This is not constitutional governance. It is power protecting itself. When lawmakers forget that they are bound by the Constitution and subordinate to the people, they manufacture crises and then blame judges, voters, or “activists” for the consequences of their own breach of duty.

This conclusion is reinforced by recent polling from the conservative Sutherland Institute, which found that 91 percent of registered Utah voters support the continuation of an independent redistricting commission to prevent gerrymandering. That level of agreement across party lines suggests the issue is not ideological, but institutional. When voters consistently express support for independent guardrails, yet governing bodies move to weaken or repeal them, the resulting conflict is not a failure of democracy, but a stress test of whether voter intent is treated as binding once it prevails.

The Bottom Line

- The voters acted lawfully

- The court acted lawfully

- The Legislature is reacting politically

Reasonable people can disagree about remedies.

But a system where voter mandates are treated as optional is not conservative.

It’s corrosive.

If voter-approved statutes don’t bind those in power, then elections become branding exercises, not instruments of self-government.

That question .. not party loyalty, not personalities … is what Utah now has to answer.

This is no longer a dispute about redistricting.

It is a question of constitutional order.

The Legislature swore an oath to uphold the Utah Constitution, not to reinterpret it when compliance becomes inconvenient. When voters lawfully enacted Proposition 4, that statute became part of Utah’s governing framework with equal force to legislation passed by lawmakers. By altering, delaying, and partially implementing that law rather than either complying with it or openly repealing it, the Legislature defaulted on its constitutional duty. That failure is what created this crisis.

Utah’s Constitution is explicit. All political power is inherent in the people. The Legislature is not supreme. It is subordinate to the Constitution and bound by voter enacted law. When elected officials act as though initiatives are advisory suggestions rather than binding statutes, they invert the constitutional hierarchy they are sworn to protect.

What makes this moment dangerous is not disagreement over maps, but the normalization of defiance. Rhetoric has overwhelmed common sense. Political messaging has displaced the rule of law. Courts are portrayed as activists for enforcing statutes. Voters are treated as obstacles when their decisions produce inconvenient outcomes.

That raises a serious question. Is it lawful for elected officials to disregard voter enacted law while claiming constitutional fidelity. The answer is no. That behavior does not preserve constitutional government. It undermines it.

Conservatives are struggling with this moment because they have been conditioned to see the judiciary, initiatives, and enforcement mechanisms as threats rather than safeguards. In doing so, many have lost sight of first principles. The Constitution does not exist to protect the Legislature from the people. It exists to protect the people from the Legislature.

Utah is not facing a political crisis. It is facing a constitutional one. The confusion is not accidental. It is the predictable result of a system that has taught its voters to defend power instead of principle.

In Summary:

This controversy exists because the Legislature defaulted on its constitutional responsibility. Faced with a voter-enacted mandate, lawmakers neither complied fully nor moved promptly to repeal it honestly. Instead, they attempted to manage around it. They altered the framework, and diluted the process while claiming adherence to the rule. That failure invited judicial intervention and guaranteed the outcome conservatives now decry.

The bitter irony is that many conservatives are now defending the same institutional arrogance that produced SB54, an elite impulse to distrust voters, sideline grassroots reforms, and assert legislative supremacy over constitutional limits, while claiming to act in the name of conservatism.

This is not constitutional governance or a victory for conservatism. It is power defending itself. It is the consequence of abandoning first principles. When lawmakers forget that they are bound by the Constitution and subordinate to the people, they create crises that later get blamed on judges, initiatives, or “activists,” rather than on the original breach of duty that made judicial intervention inevitable. They create the very judicial “activism” they later condemn, offering a textbook demonstration of political gaslighting instead of constitutional leadership.

FAQ’s

1. Is it reasonable to say legislators violated their oath?

Yes, it is reasonable to argue that their actions were inconsistent with their sworn constitutional duties. The Legislature acted in knowing disregard of constitutional limits after being put on notice, which constitutes a breach of their oath to uphold the Utah Constitution.

Speaker Schultz’s public statements minimizing or omitting the role of voters, combined with repeated engagement with constitutional analysis (such as the REPRO Legislative Report – 97% open rate), eliminates plausible ignorance.

2. Why conservatives are right to be alarmed

Conservatism is not about protecting Republican power. It is about limited government, constitutional order, and popular sovereignty

When legislators, treat voter-enacted law as optional, redefine their role as superior to the people, and blame courts for enforcing limits they ignored, they invert conservatism into managerial rule by elites.

“We know better than the voters, and we’ll adjust the rules accordingly.”

3. What remedies does Utah actually have?

Utah has very few direct remedies, and that is part of the crisis.

Available remedies (none are ideal):

- Elections

- Slow, blunt, and often neutralized by gerrymandering or party control

- Impeachment

- Constitutionally available, but politically implausible absent criminal conduct

- Judicial enforcement

- The remedy currently in play, and the one being attacked

- Initiatives

- Now under assault precisely because they constrain legislative power

- Internal party accountability

- Historically weak, selectively applied, and often performative

- Public documentation and exposure

- This is not a legal remedy, but it is a constitutional one in the Madisonian sense

There is no recall, which is why oath violations matter so much. Without recall, fidelity to constitutional limits is the safeguard.

4. The real issue conservatives should focus on

The question is not whether legislators acted legally in the narrow sense, but whether they honored the constitutional role they swore to uphold. When elected officials reject voter supremacy, evade statutory limits, and blame courts for enforcing the law, conservatism loses its anchor.

Whether through neglect, defiance, or institutional arrogance, the Legislature abandoned its constitutional role as servant of the people, and that failure, not the courts, produced the crisis Utah now faces.

One-Page Oath Analysis for Legislators

(Designed to be read, not dismissed)

Title: The Oath, the Constitution, and the Role of the Legislature

Purpose

This analysis addresses a narrow but essential question: What does a legislator’s oath require when confronted with a voter-enacted constitutional mandate?

The Oath

Utah legislators swear to “support, obey, and defend” the Utah Constitution.

That oath is not symbolic. It imposes three obligations:

- Fidelity to constitutional hierarchy

The Utah Constitution explicitly establishes that political power originates with the people. Legislators are agents, not superiors. - Good-faith compliance with enacted law

When voters enact a statute or amendment, the Legislature must either:

- implement it as written, or

- repeal or amend it transparently and lawfully

- Managing around the law while claiming compliance satisfies neither duty.

- Respect for constitutional remedies

Courts exist precisely to resolve breakdowns when one branch exceeds or neglects its role. Judicial enforcement is not activism when it responds to legislative default.

What Went Wrong

In the redistricting controversy, the Legislature:

- did not fully implement the voter-approved framework,

- altered its operation while claiming adherence, and

- delayed resolution until judicial intervention became unavoidable

This sequence matters. Courts did not seize power; they filled a vacuum created by legislative inaction and partial compliance.

Why This Is an Oath Issue

This is not about maps. It is about whether constitutional obligations are optional when inconvenient.

A legislator may disagree with voter policy. A legislator may seek repeal. But a legislator may not nullify constitutional limits through delay, substitution, or procedural maneuvering without violating the spirit, and arguably the substance, of the oath they swore.

The Conservative Test

Conservatism is not loyalty to institutions. It is loyalty to ordered liberty, limited power, and popular sovereignty. When conservatives defend legislative supremacy over voter authority, they are not preserving the Constitution… they are hollowing it out.

Value-Based Conservative Call-Out

Conservatives are facing a quiet but serious reckoning.

Either:

- the Constitution means what it says, or

- it means what power can get away with

Either:

- the people are sovereign, or

- sovereignty belongs to whichever institution is most politically insulated

Defending legislative overreach because it wears a Republican label is not conservatism. It is tribalism masquerading as principle.

The same logic that justified ignoring voter mandates on redistricting justified dismantling the caucus system under SB54. Different policy. Same impulse.

If conservatives abandon first principles whenever those principles restrain their own side, they are not defending the Constitution, they are training the next majority to ignore it altogether.

That is not a winning strategy. It is a slow surrender of constitutional self-government.

MORE QUESTIONS/ANSWERS

1. Did the Legislature’s 2025 map follow the guardrails of Prop 4, absent the commission?

This is genuinely contested, and reasonable people can disagree. The Legislature argued that its map substantially complied with Prop 4’s criteria even without a functioning commission. The trial court disagreed, concluding that Prop 4’s structure and standards were inseparable from the commission process itself. In other words, the court did not say the Legislature ignored every criterion, but that compliance could not be partial or selective once the statute was the governing framework. That is a legal judgment, not an empirical one, and it is precisely what the Supreme Court is now being asked to review.

2. Did Judge Gibson elevate her ruling into a de facto constitutional amendment?

No, not in the formal sense. She did not convert Prop 4 into constitutional law, nor could she. What she did was treat a voter-enacted statute as binding law that constrained legislative discretion. That is different from constitutional elevation, but I agree it feels similar in effect, which is why the discomfort is understandable. The distinction matters: she enforced a statute against the Legislature, she did not entrench it beyond repeal or amendment.

3. Did the Utah Supreme Court elevate Prop 4 over existing statute?

The Court did not elevate Prop 4 above statute; it reaffirmed that statutes enacted by the people and statutes enacted by the Legislature are legally equivalent. What changed is that once the people acted, the Legislature could not materially rewrite the statute while claiming fidelity to it. That is consistent with Utah precedent, even if it conflicts with a century of legislative habit. The Court did not create superiority; it enforced equivalence.

4. Is it reasonable to say there are no checks and balances because MWEG (Mormon Women for Ethical Government) is not electorally accountable?

This concern is legitimate but incomplete. You are correct that MWEG is not directly accountable to voters, and that is uncomfortable. However, the accountability chain is indirect, not absent: courts are accountable through appellate review, judges through retention elections, and remedial maps through judicial standards. The lack of direct electoral accountability is not ideal, but it arose only because the political branches failed to resolve the conflict created by noncompliance. Courts do not replace representative government unless the representative process breaks down.

5. Does this set a dangerous precedent where activists can impose maps through courts?

It is a risk, and that risk is precisely why legislative default is so consequential. But the remedy chosen by the court was not based on who proposed the map; it was based on which submission most closely satisfied judicially articulated criteria under severe time constraints. That is not a desirable model of governance, but it is a remedial one, not a permanent transfer of power.

How to Spot Propaganda in This Debate

You do not need to be a lawyer to recognize when you are being steered instead of informed. Watch for these warning signs.

1. Appeals to Authority Instead of Substance

When arguments rely on who is speaking rather than what is being said, pause. National figures weighing in on local redistricting should raise questions, not settle them.

2. Urgency Without Explanation

“Sign now” campaigns that do not clearly explain consequences are not about education, they are about momentum.

3. Vague Language About “Representative Government”

If a message sounds noble but avoids specifics, ask what power is being gained or lost. In this case, repeal removes voter-imposed limits and restores discretion to lawmakers.

4. Framing Reform as Dangerous

When a voter-approved reform is described as radical or destabilizing, ask whether it actually changed outcomes or simply limited insider control.

5. Silence About Voter Intent

If the original vote is treated as a mistake to be corrected rather than a decision to be respected, that tells you how voter authority is viewed.

Propaganda does not always lie. Often it just omits what matters most.

CONSTITUTIONAL COMPARISON

Voter Power vs Legislative Power in Redistricting

- Voters set guardrails through lawful initiative

- Politicians operate within predefined limits

- Maps are drawn using neutral criteria

- Power flows upward from citizens

- Trust is earned through restraint

Voter Power Model (Proposition 4 Framework)

Constitutional principle: Checks and balances apply to lawmakers as well as courts.

Legislative Control Model (Post-Repeal)

- Legislature and governor regain broad discretion

- Guardrails removed or weakened

- Maps may be drawn with partisan advantage

- Power flows downward from incumbents

- Accountability relies on future elections

Constitutional risk: Those who benefit from the system also design it.

The Real Choice

This is not about who draws the lines.

It is about who sets the limits.

If voters cannot impose lasting constraints on political power, then initiatives become advisory, not binding. That undermines the purpose of citizen lawmaking itself.

An Open Message to City Councils and County Commissions

Local officials across Utah are being asked to support or promote the repeal of Proposition 4. Many are doing so reflexively, out of party loyalty or institutional habit.

This deserves a pause.

City councils and county commissions exist to serve residents, not political structures. When a voter-approved reform is targeted for removal before it has fully operated, local leaders should ask one basic question:

Does this strengthen voter trust, or weaken it?

Supporting repeal may feel safe. It aligns with party leadership. It avoids conflict. But safety is not the measure of constitutional duty.

Local officials should consider:

- Whether voters in their jurisdictions supported Proposition 4

- Whether repealing it increases or reduces transparency

- Whether restoring discretion to higher offices serves local representation

- Whether silence equals consent when voter authority is being rolled back

No local body is required to endorse this repeal. Neutrality is an option. Independent judgment is an option. Constitutional fidelity is an option.

History rarely judges kindly those who say, “I was just following the leadership.”

DUAL-LICENSE COPYRIGHT NOTICE for THE REPUBLIC PROJECT

Copyright © 2025 The Republic Project (Nonprofit) and Republic Project Strategies, LLC. All rights reserved.

This publication is protected under a dual-license structure designed to safeguard its integrity, prevent political distortion, and maximize transparent public access.

I. INTERNAL & PROFESSIONAL USE LICENSE (Restricted Use)

This license applies to lawmakers, staff, advisors, media partners, researchers, and any party receiving this report directly from The Republic Project.

- No content from this report may be altered, excerpted, reformatted, rebranded, summarized, or repackaged for political messaging, campaign material, lobbying efforts, or partisan advocacy without explicit written consent from The Republic Project.

- Selective quotation or editing that distorts meaning, removes necessary context, or misrepresents the authors’ conclusions is strictly prohibited.

- Analytical, journalistic, academic, or legal-use quotations are permitted only if reproduced accurately, attributed properly, and presented without manipulation.

- Any attempt to weaponize, mischaracterize, or misappropriate REPRO’s analysis for partisan advantage constitutes a violation of this license.

For permissions, contact: republicproject.org@protonmail.com

II. PUBLIC RELEASE LICENSE (Shareable, but Not Modifiable)

This license governs public circulation via news outlets, community groups, educational institutions, and general audiences.

- This document may be shared, posted, or distributed in its complete and unaltered form, provided attribution to The Republic Project is retained.

- No modifications, edits, summaries, abridgments, added commentary, or derivative works may be published without written approval.

- Reasonable fair-use excerpts for commentary or reporting are permitted if accuracy and attribution are preserved.

- No party may present altered or partial content as an official REPRO position.

For republication requests, contact: republicproject.org@protonmail.com

III. PROTECTION OF INTELLECTUAL INTEGRITY

Both entities—The Republic Project (Nonprofit) and Republic Project Strategies, LLC (For-Profit)—retain full intellectual property ownership and enforcement authority.

The purpose of this dual-license system is to ensure:

- The content cannot be twisted, weaponized, or politically manipulated

- The public may access it freely without risk of distortion

- Lawmakers and institutions may reference it without altering its meaning

- REPRO’s research remains accurate, trustworthy, and immune to partisan misuse